@AF: His color choices would be fine, if he was skinning it so that it felt like a light. The problem therefore is how to make it feel like a lightsource, instead of just a yellow thing.

Now, if it's just supposed to be yellow paint... there's a problem. Yellow paint, IRL, generally turns brownish with staining (in fact, most things do, because what's staining things? Dirt, mostly.). Yellow also tends to bleach out, leaving it with dappled colors of yellow, yellow-white, and brown-yellows.

If it's a light, however, then it needs specific treatment, as a light source. There are two main ways to accomplish that (and Wolf's quickie is a good demonstration):

1. Use some yellow at the edges of the gray, metallic parts, using the airbrush, to convey the sense that some of the glowing yellow light is reflecting off of the metal. That's a very effective technique, and I use it constantly, when trying to convey light. It's not terribly hard- just examine your map and see where the yellow light should go. Then airbrush, using the slowest setting you can stand (I use a flow of 3%, myself) and a fairly wide brush, so that you don't end up with stippling.

2. The light itself needs to have form. Lights that are in containers have effects on the containers- what we're seeing the light come "through" in this case, since we don't yet have transparency to play with, not that it changes a lot. So, a suggestion of the source inside the form is appropriate. I'd use a lighter shade of yellow, close to white, and gently airbrush a shape on a new layer over one of the four faces (or all of them, if he mirrored well), and on the top as well. Then blend back inwards a bit with the pure yellow.

@Saktoth:

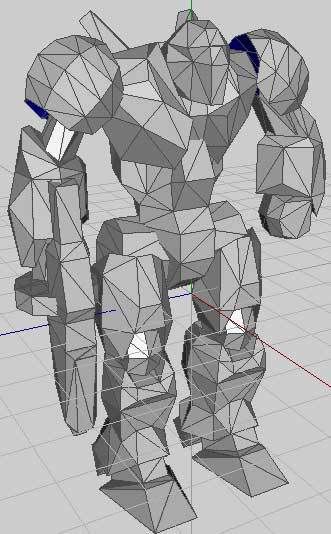

I think you're misunderstanding what we mean by "preshading" a bit. Basically, what I see you doing is creating definition of the facets, by making them lighter. That's cool, and it can bring some life to the model, but preshading isn't the same thing. Basically, preshading means that we're imagining light, coming down from above, and then creating, on the texture, the places that are in shadow. Go take a look at the Sniper Mandroid again. You will see, for example, that there's a faint but noticeable shadow underneath the "chin" on the "chest". I'm not using a raytracer- that's painted on

Preshading can help define your geometry a lot further than merely adding detail alone. It's kind've tricky at first, but well worth it. Generally speaking, for preshading, I either use a very dark version of the color I'm working with, or just plain black, and just as with light, I use a big brush and a very slow setting (if you keep your textures on a seperate layer, like I do, then you can use the Magic Wand to just work on one area at a time, so that you don't screw up the piece by accident).

As for adding interest, grime, and other little bits... well, you've greebled the model somewhat, but it needs more, to really get where it needs to go. It still feels very purple all over- it needs some panel lines, if nothing else. Panel lines, even on irregular surfaces, are easy. Just take whatever you're working on, use Magic Wand to select it, and make a copy of it. Then fill the lower version with a dark texture (NOT TRUE BLACK). Then just use the erasor on a very small scale to cut panel lines, and if you want to add more interest, apply a very small (2-3 pixels, tops) bevel, with a light amount of white / black, not the Photoshop defaults, which are generally-speaking too shiny.

Now, for adding dirt, rust, and other forms of wear... firstly, Pattern Stamp is your best friend. Get some big, tiling textures of rusty metals and dirt (they're available all over the Internet, but I use a lot of textures from

Berneyboy, who made a fabulous collection of really good tiling stuff available for free, including some excellent metals).

Use the rust, dirt, etc., with Pattern Stamp to add dirt. This part, for me, is really easy, but if you're not used to detailing stuff, you need, really need, to go look at photographic references of real-world war equipment, and what modelers do.

For a flat-out EXCELLENT reference source on how to do weathering and staining correctly,

go here, and study this man's work. He humbles me, frankly. Anybody who wants to know how to emulate wear should study his work, and I but make pale copies. It doesn't matter, that he's doing that with chalks and inks- the concepts are all the same.

Dirt and gunk is a factor of these things, on machinery, imho:

1. Dirt due to dirt being thrown onto the vehicle by its motion. This is a unique pattern of dirt, unique to the type of vehicle and the type of motion. Tanks, IRL, get very, very dirty- they fling clods everywhere, when they move at speed, and they get dirt anywhere the tracks can fling it- mainly on the sides, but also on the rear, and the front gets dirty from tanks in front of it.

A walker would have a very distinctively different set of dirt- mainly, big splashes going up the feet and lower legs. I usually take care to make the feet of mecha extra grungy as a result, although I like a patina of grunge everywhere, because it adds interest.

2. Dirt smeared by rapid motion. Aircraft have unique patterns of dirt, due to their higher speeds. Any areas that are dirty, usually due to either exhausts, gunfire, or lubricants, will show streaks that fade along the surface, perpendicular to the axis of travel.

3. Oil / Lubricant / Etc. This is grunge from a moving, lubricated part. It will generally show some signs of obeying gravity (taking gravity into account is always super-important, btw, it's one of the main things that will keep your grime coherent and instantly realistic to viewers), but it will also show signs of concentration around the part, and may show spotting, if it's prone to spit out droplets on occasion. Generally speaking, I suggest oil staining with airbrush and true black, a small brush and low speed, adding some random dots, and some stain lines following gravity or whatever imaginary geometry I've painted on (never, ever, just follow the MODEL, follow your greebles- they're just as "real" as everything else is).

4. Battle damage. I don't do a lot of this, because it can rapidly become very cheesy-looking. If every tank in your army looks like it just survived WWIII, then your game will look stupid, imo. But if you must do some, study reference shots- depending on the level of armor, battle damage looks very different. For example, with tanks... generally-speaking, either the damage is catastrophic, or it does no real damage at all. You could suggest machine-gun hits, or whatever, on a tank by Pattern-stamping metal over your "paint", then adding some dirt later on, so that it doesn't look odd, and blends gracefully into the paint. If you want craters, etc., there are lots of tutorials that teach about how to do them.

5. Exhaust systems and other sources of grime. Anything with an engine is going to produce exhaust of some sort, somewhere. Vents with dirty edges and bevels / interior shadow can tell people a lot about your design, and help convince them that they're not just looking at a fantasy. Again, take into account gravity, direction of motion, and in the case of exhaust, the fact that most of it goes UP, and therefore the staining should go up, too.

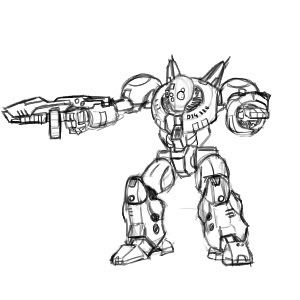

Also, while I'm ranting about random crap, here's a more practical example, showing a lot of this stuff:

Now, this isn't some sexy, giant robot, and in the stock pose, sans animations, etc., it probably looks pretty lame. However! It shows all of the technical techniques I just described, so here ya go.

Note the way that dirt is generally going down, to follow gravity, the stains defined with a few streaks around the moving parts, and the way that the stains from whatever those holes are on the wheels are all going OUT, where centrifugal force would naturally take them. In general, people... your greebles don't have to make a lick of sense, if you're not copying somebody else's design... but if your detailing doesn't take Nature into account, then it will just look random and like lame dabs of dirt.

And see the dark areas, where the corners of the pyramid are? That's preshading. I kept it subtle, and made it work with the dirt, but you can clearly see that I'm playing a trick with light there. And the undercarriage is also considerably darker than the top- again, preshading. It's actually going to be darker than it looks, in this UVMapper shot, once it's in-game, but you get the idea. Preshading is about providing as much information to the human eye about contrast as possible- our eyes actually see mainly by using contrasts to construct form, so always take advantage of that, and don't expect the Spring engine to pick up the slack for you. Many guys, they'll get stuff done to a certain point, stick it in a raytracer, and go, "it'll be fine". No, it won't... because while Spring's renderer is fairly accurate, physically, it's a direction-light, and it will not render subtleties of angle very well.

Here, you can see how I treated this light. It's not a powerful light, so there wasn't any real need to make it feel bright by "lighting" the interior of the hole. I was tempted anyhow, because I actually enjoy doing that part well, but... meh... nobody will ever see it, except here and maybe in a screenshot, it's a waste of time

Now... here... was a good time to do some light correctly:

This is the tail end of the AirFactory, and yes, that's all you get to see, for now

However, as you can see, just like the LandFactory, I wanted to give a sense that you're looking at a powerful, sci-fi rocket engine, and at the angle it is at, you will see a sliver of this fairly often, in OTA view, so I felt that it would be appropriate to go ahead and give it a decent treatment. A purist, with nothing but free time and no deadline, would have put more effort into the engines, but as you can see, I just used a very simple repeating dot tile to represent whatever the engines do- in-game, you're probably

never going to see that far up the engines, unless you're really, really bored (I was tempted to put a SmothBoob there, but refrained).

At any rate... adding interest is mainly a matter of three things:

1. Good design sensibility in general- using changes in hue and contrast to convey meaning.

2. Being aware of, and respectful of, the wonderful complexity of Nature, and seeking to emulate what happens naturally to machinery being used off-road in violent places.

3. Cheating as much as possible by using the Pattern Stamp and other tricks to save time! It's great, if you don't have anything else to do, to do something very, very slowly by hand. Cool, good for you. But, most of us want things done... y'know... today. So cheat wherever you can get away with it, and save time for the difficult areas where you really

want to spend time. For example... unless you really suck at modeling, you can, pretty easily, make high-poly models of whatever super-ridiculously detailed mechanical greebles you want. Render 'em out in a non-perspective view... import into Photoshop... scale... use grime and airbrush to blend in... voila, a super-detailed greeble, but without painstaking, pixel-by-pixel work. I almost never bother to do that, but I've done it a couple of times before, and it's much, much easier to do that. If the exact dimensions matter, most 3D software allows you to import images as a background, so bring your first work with the uvmap, after you've filled all of the model areas, to serve as the guide... keeps things simple. Just cheat, people. Wherever you can. It allows you to spend more time on the important stuff, and if you do it right, it looks as cool as doing it the hard way.